The outright reason for Sri Lanka’s current crisis seems straightforward, the island nation strapped its foreign reserves and went bankrupt, however, a niche of external and internal factors has exacerbated Sri Lanka’s economy, which has pushed the country into an economic and a political crisis, with potential local and regional security implications.

The three decade-long civil war, which ended in 2009, has certainly contributed to the current events. Also, black swan events, such as terrorism being among the first to blame, having in mind the 2019 Easter bombings and COVID-19 pandemic, have resulted in nearly paralyzing the tourism sector.

In addition, the decade-long fiscal mismanagement, toppled with the government decision in 2019 to implement the largest tax cuts in nation’s history with the aim to revive the failing economy, have slashed the value-added tax by seven percent from the original 15 percent. This additionally led to severe reduction of government revenues, inducing creditors to demote Sri Lanka’s ratings. In turn, this hindered the country’s ability to borrow finances, while its foreign reserves dwindled.

Alongside the failed tax cut policy, the accelerator of the crisis was the 2021 ban on chemical fertilizers in Sri Lanka, which aimed at balancing the annual imports, however, the move led to a significant drop in paddy yields, plummeting rice production, forcing the government to utilize its foreign reserves in order to import products. Two years after COVID-19, Sri Lanka’s economy is brought to its knees.

Besides, the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the imposed Western sanctions to Russia affected the global food and energy prices and pushed the island nation over the edge. Today Sri Lanka experiences the worst economic and political crisis since its independence in 1948, which bears the potential to reverse the development progress made within the Sustainable Development Goals framework and plunge the region into a humanitarian crisis and re-ignite the interethnic conflict.

01

Government Corruption

01

Government Corruption

The Sri Lankan government mismanagement may well be responsible for the acceleration of the worst economic crisis in decades, which forced citizens to resort to extreme measures and violence, hoping to achieve changes in the country’s national politics.

The lack of good governance of the ruling Rajapaksa family, who has been ruling the country for 17 years, disregarding of democratic values, overstaffing the public sector, as well as the series of failed economic policies, structurally weakened state institutions and the country’s national economy. Noteworthy mention is that the public sector’s employees has doubled in size in the past 15 years, with over 1.5 million employees in the state institutions, appointed with political decisions, disregarding the merit-based system, an event that fueled the country’s downfall.

Furthermore, the centralization of power of the Rajapaksas, which gradually happened over a two-decade period, resulting in members of the ruling family assuming critical government positions, have led to a gradual weakening of the central financial institution of the country, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. In other words, taking loans from international financial organizations and private investors without scrutinizing the sustainability of the mechanisms for refinancing, represent another crucial factor for the fiscal crisis of the resource-rich island nation. Lastly, family ties among top ranking politicians and senior officials certainly create risk environment for conflicts of interest.

02

Irresponsible Spending, International Debts and Inflation

02

Irresponsible Spending, International Debts and Inflation

For decades, the populist macroeconomic policies dominated the country’s economy, which led to decrease of government revenues, deficits, increased government debt, yet the money printing made the inflation rates to steadily increase.

The year 2020 marked Sri Lanka’s increased demand for foreign currency, while the ability to earn foreign currency via exports was in decline, falling to USD 1.9 billion in May 2022, compared to the April 2018 figures of USD 9.9 billion of gross official foreign reserves. In April 2022, when Sri Lanka’s government announced that it has defaulted on its foreign loans, analysts rushed to accuse the so-called Debt Trap Diplomacy by China, however, looking at the official figures presented by Sri Lanka’s Department of External Resources published at the end of April 2021,the country’s default is not solely China’s fault, knowing that the country since 1965, obtained 17 loans from the International Monetary Fund (including the pending August 2022 IMF bailout package). In fact, Sri Lanka sought to restructure its foreign debts amounting to over USD 51 billion, out of which 47 percent came from commercial market borrowings from private banks or International Sovereign Bonds, 13 percent were debts to the Asian Development Bank, and the rest owned to Japan (ten percent), China (ten percent), World Bank (nine percent) and two percent to India.

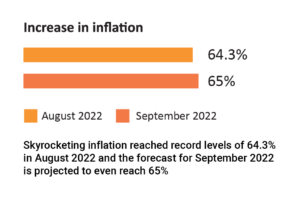

In contrast of China’s ten percent, top holders of the country’s debt in the form of International Sovereign Bonds are the US-based JP Morgan Chase, BlackRock, and Prudential, the Germany-based Allianz, Switzerland’s UBS and the Britain-based investment funds Ashmore Group and HSBC. The immense role of the above-mentioned investment funds is evident from the information provided by the Department of External Resources, disclosing the country’s foreign commitments by currency. In addition, the default weakened the national currency, and future loans were made far-flung, amid the skyrocketing inflation which reached record levels of 64.3 percent according to August 2022 figures presented by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

The Central Bank’s inflation forecast for September 2022 is projected to even reach 65 percent.

Likewise, the official data notes that food prices inflated by staggering 93.7 percent, amid the finalization of the IMF’s financial bailout package negotiations and the introduction of the interim budget in August 2022 related to expenditure and borrowing limits, with the aim to provide relief and economic recovery to crisis-stricken Sri Lanka.

In regard to the IMF financial assistance, the approval of the bailout package requires the country to restructure its debt, which certainly would not be an easy task, knowing that certain international sovereign bond holders, such as Hamilton Reserve Bank took Sri Lankan government to court, stating that it was an orchestrated default by top government officials. Nevertheless, the USD 2.9 billion preliminary bailout package, could certainly provide instant relief of the country’s economic hardships in the coming period, however the question arises whether the 17th IMF bailout package would solve Sri Lanka’s problems eventually. Undoubtedly, the country’s debt was something that the ruling Rajapaksas failed to address.

03

Ethnonationalism and nepotism

03

Ethnonationalism and nepotism

The economic crisis was further deepened with the ingrained ethno-nationalism, which enabled and bolstered corruption, cronyism and nepotism within government ranks.

Knowing that the constitution of Sri Lanka grants Buddhism a paramount power, it has enabled the continual discrimination against and marginalization of minority groups. Favoring Sinhalese citizens of Sri Lanka when it comes to access to higher education and civil services’ positions, disregarding merit, additionally festered the weak state functions. The position of power of leaders, such as the Rajapaksa brothers and Wickremesinghe was supported by the majority Sinhalese people with Buddhist ideology, yet on the other hand allowed accumulation of politicians’ personal wealth, mismanagement of the national economy and discrimination against the minority population in the country. President Rajapaksa’s initial refusal to resign, reveals his authoritarianism, which can be ascribed to Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism. These factors contributed to Sri Lanka’s current problems.

04

Covid-19 and terrorism working together

04

Covid-19 and terrorism working together

The Easter Sunday terrorist attack in 2019 where 269 people were killed, including foreign nationals, and over five hundred injured by IS-affiliated militants had a detrimental effect on the country’s tourism and remittances fell around ninety percent since 2018, further draining the country’s foreign reserves.

And if this was not enough, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic additionally hit the suffering tourism sector and the country’s national economy, which drove the country to close its borders for tourists. As a result, foreign visitors have nearly disappeared, and quarter of the total arrivals in the country were made by Russian and Ukrainian tourists.

After lifting the travel ban in late 2021, the tourism sector started its slow recovery, reaching highest levels by March 2022. Nevertheless, by mid-2022 the monthly tourist arrivals dropped again by over 60 percent, according to Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority. Similarly, to other countries, including Sri Lanka, the tourism sector is set to suffer, although there were hopes that there would be a recovery following the ease of health restrictive measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In fact, the pandemic deprived the national reserves, which were mostly spent on pandemic emergency measures. Even in spite of the introduction of a five-year multiple entry tourist visas in August 2022, to help boost the tourism in the country, relying solely on tourism in the current circumstances seems impossible, amid the raging social unrest, shortages of essentials and the country’s ability to serve its visitors.

05

The breaking point

05

The breaking point

The current Russo-Ukrainian conflict and embargo on Russia, which immediately increased energy costs, and pushed the commodities prices even higher, having in mind that the island nation’s imports of wheat are around 45 percent, and over 50 percent of soybeans are imported from Russia and Ukraine combined.

On the other hand, Sri Lanka’s export market is hugely placed in Russia, and the two warring countries are the key consumers of Sri Lanka’s tea. The country is also one of the favorite tourist destinations for Russians and Ukrainians. In addition, the disconnection of Russian banks from the international SWIFT system, impacted Sri Lanka’s tourism industry accordingly. Moreover, the ban on Russian ships docking at international ports, including Sri Lanka’s ports, meant severe cuts to wheat imports, which understandably undermined Sri Lanka’s food security. The impact of the Ukrainian war to Sri Lanka means a credit line for commodities which last shorter, and even with a bailout package, Sri Lankans would still buy less food, less fuel and less medicines.

06

Social Unrests

06

Social Unrests

The shortage of commodities for ordinary people, such as food, fuel, electricity and medicines, most of them being imported, eventually triggered months-long protests and discontent that resulted in violence and demands for resignation of the ruling political elite, due to failed political and economic policies.

The events culminated with storming of the presidential palace, as well as setting on fire the Prime Minister’s ancestral residence. The angry protesters were blaming the Rajapaksa family for incompetence and corruption, and the politicians were subsequently forced to resign their positions, while President Gotabaya fled the country to Singapore and then Thailand, meanwhile announcing his formal resignation by email.

The new government led by the newly appointed President, the veteran politician and former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, who is closely affiliated with the Rajapaksa family, extended the state emergency, in an effort to steer the nation out of the troubles, and sent requests for aid from India and China. As part of the efforts, Sri Lanka would restrict the fuel imports in the following twelve months, according to the Ministry of Energy, due to severe shortage of foreign reserves. Nevertheless, the protests continued, despite the events where protesters and their camps were being removed forcibly, and were also condemned by Wickremesinghe as illegal, stating that breaching into the president’s and prime minister’s offices, was not democracy.

07

What to Expect Next?

07

What to Expect Next?

Getting Sri Lanka back on its feet from the current political and economic crisis would definitely take some time and effort from the political elite.

The problem with the fiscal mismanagement that has been going on for over a decade, would need to be addressed with a combination of radical economic reforms, budget cuts and higher taxes, related to restoring electricity services and transportation, food inflation, and cost of living. It would also require a firm monetary policy in order to stabilize the Sri Lankan rupee.

The new government would have to deal with the immediate economic needs of the population in order to tackle the economic crisis. Restoring the political legitimacy and population’s confidence in the political elites is dependent on several things, such as Wickremesinghe’s promise to limit the presidential powers, organization of viable alternatives that uphold human rights and democracy, not forgetting the international financial organization’s efforts to help the failing country out. Widening the tax base and efficient collection of taxes are essential tax reforms that could lead the country to economic stability. Furthermore, the fiscal reforms demanded by the IMF are expected to be harsh, however, they are subject to an agreement among the major political parties in the parliament. IMF also requires political stability and debt restructuring, prior granting rescue programs to the already indebted country. This means that there needs to be a viable government, which would negotiate with the creditors. On the other hand, even in spite of the agreed IMF financial support (pending for approval), the ruling political elite could turn towards India, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia with the aim to ease the economic hardship and life in Sri Lanka, thus prevent the humanitarian disaster that is looming over the country currently.

On the other hand, even in spite of the agreed IMF financial support (pending for approval), the ruling political elite could turn towards India, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia with the aim to ease the economic hardship and life in Sri Lanka, thus prevent the humanitarian disaster that is looming over the country currently.

The announcement that the fleeing president Rajapaksa would return to the country, would be conditioned with his exemption for war crimes prosecution and protection from extradition, however, it could trigger discontent and more protests against the former President’s return to the country, demanding political accountability and criminal responsibility by activists and victim’s families. Protests are expected to continue in the coming period, despite the decision to not renew the state of emergency, which was imposed in July by Wickremesinghe. In addition, there also is a potential risk that anti-IMF protests (similar to the those in Argentina recently) could spark up with protesters demanding immediate halt to repaying IMF’s foreign debt, since the loans are perceived as a form of external financial extortion.

For Sri Lanka to break free from this crisis continuum and get back on its feet, besides the harsh economic reforms, a robust international response is needed, knowing that number of loans have been taken without realistic repayment strategies. Tackling high profile corruption, revision of policies for fair inclusion and representation of minorities, ought to be addressed, as well.

Having in mind that Ukraine and Russia are important markets for the island nation, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the resulting sanctions could additionally impact Sri Lanka’s economy, prolonging the economic hardship of Sri Lanka’s citizens, where food shortage is one of the key issues in 2022. Sri Lanka’s political failure and prominent level of foreign debts in a post-pandemic world, highlighted the risks of sovereign debts in a period of geopolitical rivalry, and rang the alarm bells to other similarly positioned countries in Asia and Africa.

ARTICLE | 15 PAGES